The Participants

Steve Holland: With the grand title of leader of the ‘Cold Weather Equipment Development’ team it was Steve’s job to plan the trials. Steve has worked with Ran since the mid-80s. An engineer’s logical approach and an open mind was the order of the day to draw our own conclusions and not just rely on the manufacturers sales material. Planning such trials and the shear amount of testing to be completed within such a short time window would be fun at the best of times; doing it without any budget makes it that more of a challenge.

Mac Mackenney: Mac was originally ‘discovered’ on a selection for one of Ran’s expeditions many years ago. He has a number of long distance driving records including that for London to Cape Town in just over 11 days. An expert in expedition logistics and equipment, Mac was one of the two ‘guinea pigs’ in the cold chamber whose comment and feedback would be a key part of our assessment. Mac now spends a lot of his time running logistics and field support for TV driving projects but still makes time for us ordinary folks.

Russell ‘Tomo’ Thompson: Tomo is an outdoor instructor with global expedition leading experience and an extensive climbing and mountaineering background. Having supported a number of clothing manufacturers he is very analytical with equipment and its performance and was used as our second chamber subject. Steve and Tomo met on the army Physical training Instructors Course so long ago that they both had hair.

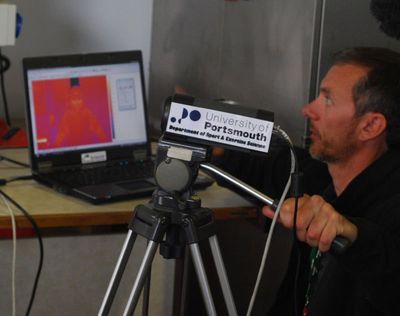

Geoff Long: Geoff had been quietly minding his own business at the Sports and Exercise Science department at the University of Portsmouth when Steve Holland came calling. We were in need of a skilled person and the equipment to record skin temperatures of the chamber subjects. Thankfully Geoff, with the support of his boss, Professor Mike Tipton, was up for this and has since become an integral part of the whole project. Geoff, as well as being the technical Mr Fixit has a love of the outdoors and has travelled extensively including cycling in the Himalayas (not sure he appreciates the advantages offered by the internal combustion engine).

Abi Holland: Having just finished her GCSEs and at the end of the summer holidays Abi was put to work as support staff, principally for Geoff. Abi has been ‘working’ on Ran’s projects since she was about three years old including being part of the support crew for the Devizes Westminster canoe race at a mature seven years old.

Steven Seaton: Steven has been undertaken many adventures with Ran. These include the North and South Pole marathons, Eco-Challenge multi-day adventure races and the classic Devizes Westminster canoe race. As editor of Runner’s World, Steven was well used to reviewing equipment and clothing. Steven was able to join us part way through out test programme and was a very useful third chamber subject.

The Location

The Plan

There is a myriad of formal test specifications that could be used for assessing the performance of individual items of clothing. To use such a formal approach would have tied up laboratory facilities for weeks and we didn’t have the time or the budget. We were also testing equipment for use only at the most extreme end of the scale, so our own personal assessment, trialling equipment side by side was our best way forward. The outcome of our chamber testing would be a recommendation on what to take for field testing in the Arctic winter. The Arctic would be the more formal qualification, this was the sifting of different technologies and designs.

The tests would be a combination of wearer trials in which opinions on comfort, dryness, ability to function etc would be crucial, backed by isolated equipment trials in which the human is deliberately taken out of the equation and the results would be in the measured data.

We will not use this platform to present specific results as this would be unfair to the manufacturers who were kind enough to offer equipment. Our tests were very much geared around our specific needs and do not necessarily reflect how the equipment will work in more normal circumstances.

Isolated Equipment Testing:

Down Jackets

These high value and complex items are hard to compare as they would never be worn without a variety of layers underneath, which all contribute to the overall effect for the wearer. To assess the jackets in isolation we needed a surrogate torso of suitable mass and predictable cooling behaviour.

For our surrogates we used 40 litre water jerrycans, all filled to the brim with water at the same body like temperature. These would be suspended from a rail so that there was no obvious heat conduction path. Geoff Long attached thermocouples to the front and rear faces of each to record the ‘skin’ temperature. Each water container was then fitted with a jacket, their bottom draw cords pulled tight and the hoods pulled over so that they completely shielded the jackets in the same manner as each other.

The thermocouples were attached to a data logger and the cooling recorded. This was our first test and whilst underway we able to sort through the mountain of gear we had prepare for the first wearer trials.

It was most pleasing to find that even with the chamber at an average -53C, a significant draft caused by the chambers own fans , further enhanced by a large blower to maximise the effect, all the jackets worked very well – indeed the experiment went on significantly longer than anticipated. There was an average drop of ‘skin’ temperature of about 4c in the first two hours – the jackets may be expensive, top of the items but there certainly work!

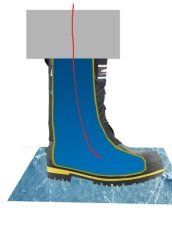

Boots

We had three high performance models to test and each was tested with and without electrically powered heated insoles. We felt that the testing of these in isolation was very important as the perception of warmth from a heated insole could be quite different from what it was actually achieving.

Following the principles used in the isolated jacket tests we used shaped sealed bag of water at body temperature as our surrogate lower limb and inserted a pair of thermocouples well down into the body of water. We avoided contact between thermocouple and skin of the bag so that we weren’t recording conduction at this surface. The boots were placed on the steel chamber floor – very conductive and a match for an ice-shelf. A foam block was then inserted into the top of the boot to control and minimise heat loss up and out of the boot.

For each pair of boots one insole was powered up just before the test started, the other left switched off.

On the graph shown the top two lines were the heated versions of the next two down, which does show that the powered insoles do provide a benefit although this in reducing the rate of heat of loss rather than preventing it.

Gloves

To test the passive insulation of the wide selection of gloves we adopted the same system of measuring the cooling rate of a body of water. Thankfully ready-made hand shaped waterproof liners were available – bring on the washing up gloves. Some of our candidates were gloves and some were mittens so the thermocouple was placed in the centre of the palm to help with comparison. This test was conducted near the end of our time and we had by then conducted a lot of wearer trials. It was therefore interesting to compare the isolated test with how the gloves seemed to perform for the wearer.

Having run this test it became clear that some more detailed investigation was required, a job carried out by Geoff back at the lab in Portsmouth.

Socks

Having run this test it became clear that some more detailed investigation was required, a job carried out by Geoff back at the lab in Portsmouth.

When assessing the gloved it was important to consider the two distinct requirements. Ran and Crevasse Detection team will be spending long periods outside and their hands would mainly be used just operate ski poles. Dexterity was secondary to insulation so large mittens would be the way forward. For the mechanics however they needed to be protected whilst performing some detailed tasks. Although they would have a set of outer mittens, they would have two layers of fingered gloves beneath. For very detailed work the inner, or contact gloves. These would stay on at all times. Even when working on warm engine it would be so easy to place an unprotected hand on adjacent nearby piece of cold metal.

Wearer Trials

What did we measure?

It is the extremities that are the first to suffer in the cold. Geoff wired up toes and fingers for Mac and Tomo. These were connected to wireless transmitter sending signals back to a laptop. This system allowed freedom of movement. It is also the case that a wired system would have been much too fragile at -53C. At this temperature it is amazing how brittle everything becomes.

We had considered core temperature measurements but in the end dismissed these as a reduction in core temperature lags behind skin temperature and would not have added anything useful to the process. Both test subjects were pleased to hear that core temperature measurement by the ‘traditional means’ was off the agenda, although we didn’t tell the so until the last minute.

Our assessment regime required periods in which the subjects would perform step ups at a moderate but consistent rate. This was dictated by an audio metronome fitted to Tomo. Mac would just keep in step. To add to the cables and complexity they were also both wearing radios with ear pieces and microphones.

A most important consideration in our wearer trials was that Mac, Tomo and Steven didn’t actually get cold. One might suggest that would be what you would expect to happen in a cold chamber but for very good scientific reasons we couldn’t allow it. If the temperature in the hands and feet drop below a threshold level then wider changes take place to the circulation within the body that then take a long time to properly reset. To make a valid comparison between clothing systems we needed to be sure that each test cycle started with our subjects in the same condition. For comparison purposes however we did not need to run each test to such limits, We only needed to get enough data to differentiate between items A and B. Also, a quicker turnaround allowed us to compare more systems and combinations. A more detailed assessment could take place later in arctic field trials or another session in the chamber.

As well as the skin temperature measurements our subjects had to complete some perception tests. At specific intervals during each session they would asked over the radio to score their thermal sensation, thermal comfort and skin wettedness off sheets on the chamber floor. These were commented on for both hands and feet.

They also had to conduct dexterity tests to see what was achievable with the different glove styles and levels of viewing restriction offered by different helmets and goggles. The dexterity text was a simple one, threading a nut onto a bolt. It was important to get an ambient temperature, ungloved baseline against which we could compare. As soon as it was clear that this was a timed activity, competitive instincts came to the fore. Then add a BBC news camera and it becomes deadly serious.

Some General Findings:

Money isn’t everything and reputations need to be challenged. This was especially the case with some of the gloves we tested. There were a couple of models used extensively in high altitude mountaineering that stunned us with how bad they were, indeed they were repeat tested just to be sure. Conversely other gloves showed themselves to be very good and beyond our expectations.

The Paramo system worked very well. People seem to either love or hate the Paramo cold weather clothing. We tested it against what we called the more traditional rig of base layers and fleeces. We were more familiar with this approach and somewhat sceptical on the Paramo system. We can say now that in very cold, dry circumstances it worked very well for both static testing and when worn during sustained exercise.

Our requirements are more extreme than most, so as a final layer of defence against the cold we selected the PHD range of down clothing. It says a lot for the capabilities of their gear when it gets too warm to exercise in it at -53C!

Helmets are good but the demisting of the visors is a challenge. The cold chamber is a very noisy place and so was a good test for quality of radio communications. After the first few tests which featured hoods and goggles we moved onto skidoo helmets with heated visors. The comms immediately became clearer and we knew that helmets would also give us a good platform on which to mount lights and provide protection to the head in crevassed areas or for higher risk activities such as kite skiing. Managing the demisting of the visors and goggles was an ongoing issue in the chamber although further field tests in Sweden did seem to result in a viable solution.

The heated gloves and insoles were a definite benefit but should only be used for keeping a warm person from getting cold. They are not effective in re-warming a cold person’s extremities and indeed working with University of Portsmouth has shown us that warming the hands and feet without warming the rest of the body can be dangerous. Local cellular activity is encouraged but the blood flow to and from the limb is still restricted leading to a build up of toxins in the heated areas.

Conclusion:

The chamber trials allowed us to select the equipment for our field trials in Sweden. They highlighted areas for further research both for Sweden and a revisit to the chamber some time nearer the departure date.